[3d-flip-book mode=”fullscreen” urlparam=”fb3d-page” id=”821″ title=”false”]

Full Print Issue

Read the full print issue as an interactive PDF

Read the full print issue as an interactive PDF

[3d-flip-book mode=”fullscreen” urlparam=”fb3d-page” id=”821″ title=”false”]

Image: Hermit Thrushes performance, Turner Gallery, Alfred University, NY

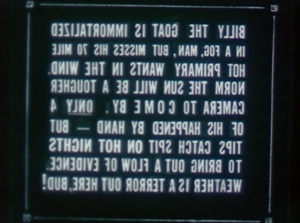

A selection of fifteen of the eighty-two hand-painted slides. For each show we projected two static slides and had one carousel of eighty slides that our viola player, Andrew Keller, advanced using a remote that he pressed with his foot throughout the set. The setup was different in each space (we played a varied mix of art galleries, bars, colleges, coffee shops), but this was the general idea: two static images and one that changed at irregular, improvised intervals.

More information at sgmgrecords.com

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

A collaboration with Denver’s Ejection Seat Collective, realized and conceived in response to the Larimer Lounge, a commercial music venue and bar.

Ejection Seat Collective from TV YAWNER on Vimeo.

The purpose of this writing is to informally theorize and expand upon the experience of the cinematic by means of extending concepts I recently discovered during a collaboration with Denver’s Ejection Seat Collective realized and conceived in response to the Larimer Lounge, a commercial music venue and bar. Although the performance was not initially conceived of as a cinematic experience it resulted in a documentary video piece which contains potential for cinematic experience gleaned from a multimedia environment by using the modular concept of the performance and applying it to the cinematic environment. This is done primarily by sacrificing the purity and sanctity of modern art and bringing it into contact with what I will call ‘pop-cultural architecture.’ This significantly changes the performance by allowing it to respond to different environments, technology, architecture, performers and most importantly audiences.

Modern art demands much of its audience, which is one of many reasons why its audience is so narrow. This fact can be looked at optimistically, as an indication of high standards in the art world, or pessimistically, as an indication of irrelevance where these standards, imposed by art institutions and academia, create a narcissistic audience that wants validation of its own worldview in the blank mirror of contemporary art. While I would maintain that both of these scenarios (among others) are true simultaneously, this argument will situate itself in the latter simply because it creates an opportunity to make art outside of the institutional critique of academicism and potentially create more popular contact with art thereby expanding its impact. It is possible, if not likely, that the art gallery and museum could become the substitute religion for which it has positioned itself in the western cultural milieu, but the importance of aesthetic experience is too important to be left to chance.

The context of the experiment evolved organically; a band I played in had no drummer and would be forced to cancel an upcoming show. I asked my bandmates if they’d like to instead work on a collaborative piece with Ejection Seat as a substitute work. This would employ a subversive tactic by substituting Ejection Seat’s performance for what the Larimer Lounge and its booking agent thought would be our band. We had reasonable expectation that it would work because of the exploitative nature of the music industry as it is manifest in bars and clubs where musicians are paid poorly if at all and are booked without contractual or other protection. This practice effectively exploits an oversaturated ‘amateur’ market of bands without fair compensation as volunteers with no clearly outlined benefits. The other edge of the sword was that there‘d be no repercussions for our substitution as we were booked on assumption alone.

Both the collective and my bandmates were excited by the possibilities. It represented an opportunity for the collective’s visual and performance inclined artists to respond to a space outside the traditionally neutered white walls of a gallery. Conversely, instead of performing as a traditional underground pop band my bandmates were being asked to contribute to a performance that expanded notions of music through improvisation and experimentation and shifted focus towards its performative aspects outside of the conception of a ‘band playing a show.’

To a large extent my goal was a subversion of the assumptions aimed at two separate and marginalized creative communities; the underground rock n’ roll or ‘indie’ band and the avant-garde artist. Both communities face continual attempts at commodify¬ing their work that in neither case is in any way a commodity. Thus my band, Ejection Seat and my own divergent creative practices had common ground in cultural and capitalist assumptions about the value of our work.

Questions arose which were and remain relevant because they’re aimed at cultural assumptions; one would never assume that a hiree in training at a business wouldn’t be paid for training. Are we obligated to commodify our band by playing when booked, especially when only nebulous obligations (an implicit promise of exposure, free advertising, a few free beers and guest list spots) have been made towards us? Should artists continue to pursue creativity and aesthetics in isolated art institutions safely cloistered from popular audiences and economic viability? Why are either of these scenarios pursued in lieu of others? Why haven’t other models been considered or created? What might these models be?

A host of other questions remained but these seemed prescient at least to our local situation at the Larimer Lounge and it was now clear to me through defining the problem that one could find all of these assumptions thoroughly embodied in the ‘pop-cultural architecture’ of the music club itself. By this terminology I’m referring not to any specific aspect of the music venue and bar but rather to all of its accumulated characteristics both material and immaterial. This includes the booking agent, admission price, bartenders, which drugs were used, the audience, sound guy, other bands, architecture of the building, audio equipment, lighting, urinals in the bathroom, flyers on the wall, etc. ad infinitum. The microphones were positioned in front as a cultural arrow of expectation that a singer would sing, a band would take the stage and place their instruments by their respective mics to be mixed down by the sound guy. The audience would pay to get in and engage in drinking from the well placed bar, watch the band from in front of the stage, clap between songs and go piss in their gender assigned bathrooms, all in a rehearsed, decidedly capitalist ritual of entertainment.

The premise was no longer a band performing with this ‘pop-cultural architecture’ in tact, influencing the creative decisions of all involved (including audience, sound guy, etc.) nor avant-garde performance artists in the white-walled gallery. We would take the Larimer Lounge for what it was; a large collaborative sculpture that embodied cultural hegemony against unrestricted creative expression in social and economic terms. The notion instilled a slightly transgressive but empowering freedom and opened up a fecund creative ground of ideas.

I decided to further the critique by proposing a ‘band’ where members were replaced by single performative modules. My bandmates and Ejection Seat would submit proposals and accepted ones would become a module of the band. The ones not involved in the band could act as planted audience members and perform as a group off-stage. The only stated goal was for each performer to realize ‘authentic creative expression in the specific pop-cultural confines of the Larimer Lounge.’

The fecundity of the idea became most apparent when brainstorming for the project yielded myriad options for performing that seemed poetic, evocative and relevant to our critique. Stefan Herrera suggested repeatedly spilling beer from the cheap plastic pint glasses used by the club to prevent the audience from breaking glass ones, David D’Agostino decided to print declassified NSA documents on flyer sized paper to be made into paper airplanes for throwing during the performance, Luke Leavitt suggested that members bark ‘art’ like seals in surrealist mimicry of applause, Mango Katz and Laura ‘Babsie’ Gardner proposed a strange Dionysiac ritual aimed at music’s oppressive cult of celebrity by cryptically worshipping Amanda Bynes’ menstruation. Non-artists and musicians participating had equally potent creative vision for the collaboration. Although disparate, each module presented its own subversion of the pop-cultural architecture of the music venue as one module of a ‘band’ with expanded creative goals. To present visual cohesion in the ‘band’ I suggested we wear mostly white and paint our visible skin white with no particular associations in mind. This performance would be documented by a hired videographer on DV tape. Here we had in mind the traditional idea of documenting work in the way that many performance artists have had videographers testify to an event.

Summarily this is the outline and conceptual basis from which we gave an experimental performance on June 30th 2013 at the Larimer Lounge as an opening ‘band’ for Shannon and the Clams (from Oakland, CA) and Fingers of the Sun (Denver, CO). The actual performance changed significantly from its conception through improvisation and uncontrollable factors. It was perhaps more musical than we initially desired and achieved in rehearsal because of the sound mixer’s intervention in amplifying the most ‘musical’ parts of our soundscape. Despite this most participants felt that it was successful in creating an authentic creativity and it solicited strong reactions from various audience members, the sound man and Tom Murphy, a music critic for Voice Nation’s Westword periodical. Ironically, Mr. Murphy’s review along with other elements of pop-cultural architecture reduced the performance to a novel experimental band, albeit an interesting one by his account (he refers to us in the article as The Matildas, my band for which we substituted the Ejection Seat Collective). However in other ways the experience opened up new avenues of aesthetic experimentation informed by culturally hegemonic spaces for myself and other participants.

Although far from describing the totality of the performance, the documentary video remains an interesting artifact as a sort of freeform response to the performance from the point of view of a specialized audience member (it should be noted that a trope of this argument is that the audience is as performative in pop-cultural architecture as the performers are themselves). To the extent that it may be called cinematic, it is a cinema informed by the space in which it was realized and created out of obligation not to aesthetics but cultural space.

It is interesting to me that the videographer found nothing salvageable in the footage that he felt was usable in creating a video, which is to say only that it differed from his personal aesthetics. Although the footage is closest to documentary in nature (as a strange form of concert footage, perhaps) the piece departs from any traditional forms in that the videographer himself was conscripted into the performance as part of the pop-cultural architecture in much the same way as the sound guy was. Whether or not they would undertake the collaboration on their own (as the videographer’s comments suggest he seemingly would not) both were obliged to as part of the milieu of the Larimer Lounge. Both were hi-jacked into creative additions to our performance as part of the cultural assumptions we were reacting against. Thus the video arises as a testa-ment to a dialectic between the performance and the pop-cultural architectonics themselves where the power structure is temporarily reversed in favor of the artists and musicians with their conscripted collaborators and captive audience.

If there is anything in this experiment that is applicable to an expanded conception of cinema some¬times known as experimental cinema it is the conceptual model of subverting the architectonics of cultural space in favor of the marginalized artist. This is maybe most easily understood as a form of the Situationist International’s détournement where cultural space is recouped instead of advertising slogans. Cinema, in its much proclaimed ‘death,’ (which may be more accurately described as a fragmentation of audience) at the technological hands of computers, cell phones and tablets is in a no less marginal state. As an artist and filmmaker the questions begin to ask themselves: What is the cultural space and corresponding cultural assumptions that, begging for rupture, create a negative space for cinema? What aspects of cinema can be removed from its womb-like black box (akin to the gallery’s neutering white walls) and translated more effectively into other cultural spaces? Who are the conscripted collaborators that will enrich its experience? Which collaborators can free it from the burden of auteurism? What audiences can be blindsided by its virtue?

While some of these questions may be answered in part or whole outside of my own experience and knowledge, on a macrocosmic level they remain relevant. It’s time for art and cinema to venture out of their white walls, black boxes and ivory towers and attempt to find wider audiences through subversion if necessary. Although this is one small attempt, I am sharing it in hopes of dialogue, refinement, shared experience, collaboration and rhizomatous growth.

Trevor ‘TVY’ Jahner

Thanks to Ejection Seat Collective and especially Robin Edwards, Ben Donehower and David D’Agostino.

Photo by Tom Murphy

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

Essay with excerpts from Lawrence Jordan’s film Circus Savage — reflections by John Davis.

“The Screen flashes into light and with the picture consciousness passes across the world. The lie of the stationary photography is corrected, time is denied, partially at least, and space is unable to boast and swagger as it loves to do. The cinema frees and extends the consciousness, restores the past, and sets distance close beneath the eyes. Only the watching self remains, pregnant symbol in the darkness.”

– Algernon Blackwood

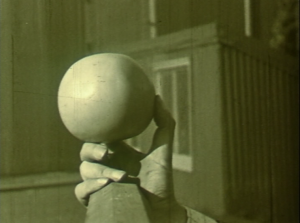

Circus Savage is filmmaker Lawrence Jordan’s confluence of moving image and sound. It is a twelve-hour assemblage of personal vision, and a privileged window into a life uncompromisingly dedicated to poetic investigation. The film itself is comprised of Jordan’s own outtakes, unfinished works, appropriations and various odds and ends. As a collagist masterwork in its own right, the soundtrack was culled from hundreds of hours of film sound, 1/4” magnetic tape and vinyl LP’s that Jordan collected over the years. While he is neither a sound artist nor a musician in a formal sense, watching Circus Savage reveals that five decades of creating time-based art has nurtured in him a lyrical adaptation to sound as well as film. From the start, discordant pairings of picture and sound prove unsteady groundwork that quickly detours our expectations, leaving us to fend for ourselves with regard to any understanding of what the film is all about. Some of the sounds are recognizable, some are not, but like their image counterparts, they question each other in a constant back and forth that leaves us little room for intellectual musing. However hard we seek to analyze the work, this is a sensory film, and viewers are best served by allowing it to envelop rather than inform.

As might be expected, there are less compelling points in the film where the rhythm falters, where extended shots of travel excursions, garden sequences and archival footage seem to meander aimlessly. In fact, the very first ten minutes of the work, extracted from Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête, is taken out of order, disarranged, and appears nonsensical. Though aligned with sounds that charge the clips with a fervent power (in this case canned sound effects), longer passages like these can appear less vital. When taken as a whole, however, these spans serve an important function, and provide the attentive viewer an opportunity to meditate on the breadth and scope of the work, to let the experience percolate in the subconscious, much the way the passing of time, memory and nostalgia might. That said, the film should be experienced rather than endured, and Jordan has stated that he expects people to come and go during screenings, to take the work in parts rather than as a whole. In fact, Jordan himself has never viewed the film from beginning to end.

I met Lawrence Jordan in 1998 while taking one of his film classes when I was a graduate student at the San Francisco Art Institute. It was the first experimental film class I had ever taken, and although I had shot film over the years, his class revealed to me a deeper world of avant-garde cinema, and fundamentally changed the way I thought about film as an art form. Then, in 2007, while I was working as a film projectionist at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, I had the good fortune to catch up with Jordan while projecting a newly struck 35mm print of his film Our Lady of the Sphere, which was being shown in conjunction with the Joseph Cornell exhibit Navigating the Imagination. Around that time I had a cassette of my own music released, and gave him a copy as an example of what I had been up to. I didn’t think much about it until I got a phone call from him some months later saying he was working on a new film called Cosmic Alchemy that he was trying to find the right soundtrack for. He went on to say that he’d listened to the tape I’d given him while doing some editing for the film, and was struck with how well the music and images worked together. He asked if I wouldn’t mind letting him use some of it for the film (I pretended to think about it for a minute), which of course I agreed to.

That opportunity wound up deepening our friendship and began an ongoing collaboration that now includes soundtracks to four films, a live music/film performance, as well as an upcoming film and soundtrack due out in July 2014. The exchange also provided me a window into Jordan’s creative process. He explained that the unsolicited act of me sharing my music was a preferred mode for him to choose a soundtrack. He went on to say that in an unconscious sense, things revealed themselves to him when they were ready, as opposed to him having to make premature choices about things when they weren’t. He said that this positioning himself to chance encouraged providence in his work, and that it was his desire to let the subconscious drive his artistic process. He further explained that my music had found the film at the right moment, and his choice, as it were, was an involuntary one that allowed the music to become a part of the film. As esoteric as that may sound, it is in fact a functional belief system that informs all of Jordan’s work, if not most expressly in Circus Savage.

I had the good fortune to project Circus Savage at the now defunct Gallery Extraña in Berkeley in 2009. Jordan, Brecht Andersch and myself ran the film in shifts for the full twelve hours, giving everyone there an opportunity to experience the work the first and only time it has ever been shown in its original 16mm format (as of this writing). The film consists of thirty-two twenty-minute film reels, as well as thirty-two twenty-minute sides of cassette tape (one twenty-minute side per film reel). Jordan’s only instructions were to take our time, to be sure and hit play on the tape machine approximately at the beginning of each reel, and to keep the cassettes and film reels in order. That was basically it. In addition to the film reels and cassette tapes (organized in a small case with drawers), Jordan brought his own 16mm projector, cassette player, McIntosh amplifier and two large speakers from his home studio in Petaluma.

When I first heard about Circus Savage I was skeptical that a twelve-hour experimental film of outtakes and unfinished works would hold up. However, I was quickly lured by its array of images and sounds, and I was struck by the fact that here was a well established filmmaker in his late career going back over a fifty year stockpile of accumulated footage to uncover it’s relevance as a new work of art. That alone is interesting, if not unprecedented, but what I found even more engaging, and what I continue to marvel at, is the tension between what appears as a seemingly random collection of forms, but is in fact Jordan acting as a divining rod for his own subconscious truth. As the film unfolds, we become untethered, drifting well beyond the reassuring harbor of any narrative anchor. This experience is disconcerting, even uncomfortable at times, but it is also liberating and charged with the excitement that comes with the unexpected. Despite all these disjointed excursions and disparate forms, it is reassuring to know that Jordan has spent most of his life embracing the subconscious as a guide through the artistic process. Jordan’s work is as much a doorway to his subconscious as it is to our own, and Circus Savage is perhaps his most well crafted roadmap for encouraging that journey. Jordan further explained his process to me as a walking into the becoming, which he said was taken from a Taoist concept that he applies to both his life and his art, and is rooted in “simply letting things happen, not forcing or analyzing, just allowing”.

Through its collection of flawed experiments, playful artistic gestures, outtakes, archival footage, and various intimate flights of fancy, Circus Savage invites us to engage fragments of a personal history. However, in an inversion of what we might anticipate, the material is decontextualized and stripped of sentiment, used less as a diaristic exposé, and more as objective fodder for Jordan’s creative explorations. This is primarily the result of the ways the sound impacts the images and vice versa, each serving as a dialectical counterpart to the other. What remains conspicuous is the familiar mirror with which to reflect our own experiences, but what also emerges is the deep humanness that comes with freely sharing one’s creative process, especially one so deeply rooted in subconscious experimentation. Additionally, Jordan’s using these expositions of film and sound as source material (some of which I suspect revealed long dormant emotional states) shows a reconciliation of, and coming to terms with the past, reinforcing a highly evolved spiritual and artistic equilibrium.

I experience the film as one largely about love. Not just the love Jordan freely demonstrates for his partner the poet Joanna McClure (who features prominently throughout the film from the 1950’s through the 1990’s), but also a love for the senses, the mind and creative expression. Simultaneously, I see the film as being about chance, both in terms of the way Jordan assembled the work, but also as an analogue to the unexpected reversals and changing currents that impact our lives, sometimes rewarding, other times disastrous. If you let it, the work is an excursion for the senses, promoting unique discoveries that can sometimes feel custom tailored to our own personal fancies.

In the end, Jordan is the experimenter experimenting with the experiment, trusting the viewer to fill in gaps, loosen expectations, and ride alongside the mystical portals of celluloid magic and it’s companion sound. Instead of recapitulating this trove of past sounds and images, Jordan re- experiments with them in order to create something new. Rather than use the past as a private memory, he shakes off its emotional weight, and allows himself (and us) to explore it in the same way he would any other source material. Diving into this personal archive and letting it choose its own final form is much the way Jordan has approached his life, and it serves as a good example of what it means to let go and be free of the suffering that comes with control, to become liberated agents on a path that has no beginning, no end, or any outcome we could possibly predict.

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

A digital compilation of film-related sounds curated by Mike Reisinger for Sleeping Giant Glossolalia.

A mix curated by Mike Reisinger for Sleeping Giant Glossolalia.

Exploring the relationship between experimental audio recording and adventurous filmmaking, On Sound features unreleased and rare material from an eclectic and far-reaching assortment of artists from around the world.

1. Bobb Bruno – “Shut Ins” 05:14

2. Anthony Di Franco “Atmospheres” 05:36

3. MjolniirDXP “Erosion The Owl” 10:56

4. Mons Meg “Drying Out” 13:35

5. New Firmament “Complete Before Light” 09:02

6. Quttinirpaaq “Lifestyles USSA” 11:02

7. The Stumps “Brave New World” 10:08

8. Fill Jackson Heights “Roosevelt” 06:39

9. Nassau Coliseum “Linguafœda” 11:44

10. A.M. “Take My Tide” 03:12

11. Les Temps Barbares “Medusa” 11:18

12. Final Boss “Break North” 02:44

13. Bonnie Mercer “I Wish I Might” 07:11

14. Bludded Head “Life’s Work” 08:42

15. Ornament “Feel Free” 04:41

16. Equine “Zaueril mit Talerschwengen” 05:02

17. Dim Wist “Future Rickshaw” 05:43

18. Paintings of Windows “Pines” 07:39

19. Ernest Gibson “Overlocale” 01:54

The 2nd print edition of Canyon Cinemazine no.3 contains a download of the album. A cassette edition is forthcoming.

More about Sleeping Giant Glossolalia on their website: http://www.sleepinggiantglossolalia.com/

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

A historical and scientific exploration of sound studies.

In Montignac, France, can be found the Lascaux Cave which dates back to the beginning part of the Upper Palaeolithic Age, a ‘time when modern mankind first emerged’ (Bataille, G., 1995, p.11) and ‘the human voice first began to make itself heard’ (Bataille, G., 1995, p.49). Lascaux Cave ‘illumines the morning of our immediate species’ (Bataille, G., 1995, p.11). Working with stone, human beings made a breakthrough that was the beginning of their separation from the animal condition. Inside the cave, Lascaux Man engraved and painted naturalistic depictions of animals. These engravings and paintings offer a beginning language that firmly anchors prehistoric art ‘in the stream of time’ (Bataille, G., 1995, p.28). Bestial mankind was at the beginning of a long road which led to the dawning of the mystical homo maximus, and, in turn, began to develop a concept concerning the ‘division between art and nature’ (Abraham, L., 1998, p.11). According to Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematist Manifesto (1916) ‘the savage’s primitive depiction gave birth to collective art […] art of repetition’ (Danchev, A., 2011, p.107). The savage being the first ‘to establish the principle of naturalism […] drawing a dot and five little sticks, he attempted to transmit his own image’ (Danchev, A., 2011, p.107).

Near the end of the nineteenth century in the United States, ‘hearing educators and reformers waged a campaign to eradicate’ (Baynton, D, C., 1996, p.1) sign language ‘by forbidding its use in schools for the deaf’ (Baynton, D, C., 1996, p.1). The basis of their argument involved ‘fundamental issues as what distinguished Americans from non-Americans, civilized people from ‘savages’, humans from animals’ (Baynton, D, C., 1996, p.1). The reformers wanted to eliminate ‘the use of sign language in the classroom – and to replace it with the exclusive use of lip- reading and speech’ (Baynton, D, C., 1996, p.4). The opponents of sign language believed the deaf ‘could learn to function like hearing people’ (Baynton, D, C., 1996, p.6). There was the idea that Deaf people inhabited a barren land of darkness.

Facts concerning Deaf people:

1. Few deaf people hear nothing

2. Hearing loss is not uniform across the entire range of pitch – while some people will hear high sounds better than low sounds, other people will hear low ones better than high ones.

3. Sounds may be distorted but heard nevertheless.

The idea that Deaf people live in silence is a tag given by the logo-centric, and as a description of their experience is meaningless. One can also note that ‘western culture equates speech with civilization itself, gendering speaking as masculine and silence as feminine’ (Glen, C., 2002, p.261)

John Dee (1527 – 1609) was an alchemist, natural-philosopher, astronomer and mathematician. He ‘believed that the universe was written in the language of mathematics’ (Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009, p.329) and that physical matter and spirit were interconnected. Alchemy was generally considered to be an art. It was the science of the day. The word science did not exist in its modern meaning until 1725.

The list of his achievements include:

1. The first English translation of Euclid’s Elements.

2. The first person to apply geometry to navigation.

3. Coining the phrase ‘British Empire’.

The Roman Emperor Caligula, whose speech was at times ‘incomprehensible’ (Winterling, A., 2011, p.5) and whose perception of reality was ‘disturbed’ (Winterling, A., 2011, p.5) made the insulting act of dressing as Venus and ‘making a horse a member of the Roman Senate’ (Kuspit, D., 1988, p.173). By doing so he destroyed the institution by making its audience doubt the Senate’s authority, raising doubts not only of the ruling class but also himself. His actions however, ‘no matter how noxious to others’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.39) they were, only ever led him ‘over and over again, back to himself’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.39). The reason why no one intervened in stopping Caligula’s murderous and suicidal action was because any accusation that would of arrived from his action, ‘would not have had to be leveled’ (Winterling, A., 2011, p.5) towards Caligula the Emperor, rather towards ‘the society that surrounded him’ (Winterling, A., 2011, p.5). To the senators and patricians, he remained ‘nothing more than a danger’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.40).

In Camus edition of Caligula (Le Malentendu Suivi de Caligula, 1944), ‘Caligula speaks in the tones’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.38) of a dying swan. When addressing Caesonia, he says that he knows that man feels anguish, though has no understanding of the word. Continuing with how he ‘fancied it was a sickness of the mind’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.33). Caligula’s whole body is in pain and he feels like vomiting. He can taste a mixture of death, blood and fever in his mouth. Realizing how ‘hard, how cruel it is’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.34) the ‘process of becoming’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.34) a man. He had thought himself free, though realizes ‘his is the wrong freedom’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.31) for it has been ‘at the expense of others’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.31). He ‘weeps for the world and all its unnamable, disfigured failings’ while at the same time ‘he weeps in despair and in pain for himself’ (Harrow, K., 1973, p.33). With his sister’s death he can no-longer recognize himself.

The singer Diamanda Galas describes her singing technique as: ‘different processes of severe concentration, ‘mental’ or ‘sentient’ states’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134). She continues by saying ‘as an artist I have to create what I see and what I hear – what’s grounded in reality’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134). Galas’ art is steeped in her Greekness and shadowed by lamentation of that exact same heritage. That heritage cries a society where women ‘occupy a contradictory position’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134) within it.

A woman’s figure is central to the living family and to the ‘rituals of mourning the dead’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134). ‘During the mourning process’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134) women’s lives are restricted because of the ‘Greek notion of death’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.134). In Greek culture the belief is held that there are three phases of death: separation, transition and incorporation. In all three phases ‘women sing laments and tend the grave’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.135). According to Holst- Warhaft: ‘there is a gender-specific tension between a woman’s lamenting voice and the institutions of the modern state.

In Galas’s songs, the listener can hear ‘this ancient antagonism that pits the voice of women against the law of the state’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.136). The sharp cries, sobs, intakes-of-breath are very much part of the lament and Galas transposes these elements into her art. To quote Holst-Warhaft: ‘Words are repeated, or nearly repeated, like incantations […] the muttered spells of witches’ (Middleton, R., 2006, p.137).

Charles Segal draws attention to the fact that many Greek tragedies ‘end with scenes of lamentation’ (Griffin, J., 1998, p.193), which release a torrent of emotion, that provides the audience ‘a satisfying […] resolution for a ‘tragic’ work’ (Griffin, J., 1998, p.193).

In 1982 in Jiangyong, Hunan Province, China, the Chinese scholar Gong Zhe Bing discovered Nushu. According to legend Nushu had been started by a young female named Ci Zhu, who had ‘been denied access to education in which she could learn official Chinese han zi characters. Another legend tells that a concubine named Hu Yu Xiu (1086 – 1100) was sent for by the Emperor for her literary skills. An example ‘allegedly written by Hu’ (Fei-Wen, L., 2004, p.425):

I have lived in the Palace for seven years.

Only seven years.

Only three nights have I accompanied my majesty.

Otherwise, I do nothing…

When will such a life be ended, and

When will I die from distress ?

My dear family, please keep this in mind:

If you have any daughter as beautiful as a flower,

You should never send her to the Palace.

How bitter and miserable it is,

I would rather be thrown into the Yangzi River.

(Fei-Wen, L., 2004, p.425)

The Emperor’s concubines were not allowed to send messages out of the palace. Hu invented a script which would get past the guards. The script needed to be chanted in Jiangyong dialect in order to make sense.

Nushu was both a visible and audible language used by females in rural Jiangyong who sort to articulate their lives through the use of singing, chanting, lamenting and writing. Nushu was able to bring womens experiences together by ‘appealing to a sense that misery was a collective female destiny’ (Fei-Wen, L., 2004, p.432). Men could neither read or write nushu. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) ‘nushu was condemned as ‘witches writing” (Fei-Wen, L., 2004, p.424) the Red Guards destroyed any nushu writings they found. Chinese male historians and literati dismissed nushu literature on the grounds of it being female-specific. In effect silencing the women of the past.

It is often thought that human language fails ‘in its capacity to represent transcendent reality’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.1). Chien-hsing Ho suggests this is a result of there being ‘aneed to distinguish between what we can clearly say and what we must eventually pass over in silence’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.1). Any supreme truth or reality is believed, in Mahayana Buddhism, ‘to be beyond the reach of words’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.1). Supreme truth, in this sense, ‘corresponds to […] what can be said using language and what cannot’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.5). The supreme truth can be seen as suchness which can be found in Buddhist philosophies. Suchness is inconceivable, the true nature of things that flows into the universe.

The teaching of the Dharma by Buddha, tells of two truths: ‘supreme truth (paramarthasatya) and conventional truth (samvrtisatya, vyavaharasatya). This can be further explained in terms of ‘conventional truth is truth in conformity with language’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.4) whereas ‘supreme truth […] does not fall into the confines of the signifier and the signified’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.4).

There is also a clear-cut distinction between what is thought to be conventional speech and sacred quiescence. Silence is used to convey what ‘is beyond thought and language’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.3) and is a ‘manifestation of wisdom rather than a result of ignorance’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.3). Silence is

‘dependent upon and correlated with speech and must not be given an overly privileged status’ (Ho, C, H., 2012, p.3).

Ekphrastic poems often start ‘from what is in the painting and as trying to transpose its visual forms to their own verbal medium’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.226). The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote in his Notebooks ‘O Christ, it maddens me that I am not a painter or that painters are not I’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.228). Coleridge was writing in a period which was supposedly more free from pictoralism, though words often failed him when trying to ‘define […] parallels […] between the ‘sister arts’ of poetry and painting’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.226).

The visual and immediate impact of painting, along with the signified silence ‘aroused the envy of the poets’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.228). To quote Charles Tomlinson: ‘When words seem to abstract, then I find myself painting the sea with the very thing it is composed of – water’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.229). The philosopher Theodor Adorno commented after, and in connection with the Nazi Holocaust, that attempts to write poetry were ‘barbaric’ (Mirzoeff, N., 1994, p.21). Many survivors thought ‘that in the face of such enormity, only silence was appropriate’ (Mirzoeff, N., 1994, p.21).

A fragment of that enormity can be seen in the film documentary Night and Fog (Dir: Resnais, A., 1955) which uses original footage shot both before and during WWII by the Nazis, who used the camera as a weapon to further dehumanize the silenced souls of men and women caught in somebody elses war.

In 1914 the scholar Michael Sadler noted about WWI to a friend: ‘There is no parallel to the horror of it in history. I daresay you don’t believe in the Devil as devoutly as I do – but in substance you’ll agree that this is a sudden outbreak of the powers of evil…’ (Higginson, J, H., 1958, p.126). Another of his notes, this time written in 1940, concerning WW2: ‘Two things strike me deeply in these days – the Reality of Good and the Reality of Evil’ (Higginson, J, H., 1958, p.126). Sadler believed that both were ‘devine in intemsity and in category’ (Higginson, J, H., 1958, p.126).

Daniel Libeskind’s design of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Germany was inspired by Walter Benjamin’s essay One-way Street which was written between the years 1923 – 26. Benjamin commited suicide in Portbou, Spain, fearing the Spanish authorities would turn him over to the Nazis. The essay ‘mapped out a whole new field of exploration outside the narrow confines of academic disciplines’ (Prouty, R., 2006). The outside of the museum’s walls have slashes which give the building an appearance of having silent wounds. The slashes allow daylight into the interior, where one also encounters voids and where one hears echoes of the past resonating inside the self.

As the poet walks through a museum, according to Howard Nemerov, he sees and hears ‘two things: silence and light’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.229). The poet sees in his own work his impatience and opinion. In silence there is spirit, whereas in the language of poetry ‘superiority to art in expressing the non-visible is reversed into an inferiority’ (Sandbank, S., 1994, p.235).

Our civilization, in the words of Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka, has been turned ‘away from a focus on ‘greatness’ and toward an appreciation of the ‘common’ human being’ (Tymieniecka, A, T., 1993, p.xi) who is part of the mass, part of the revolt which is ‘against political and social tyranny’ (Tymieniecka, A, T., 1993, p.xi).

Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893 – committed his last revolutionary act – suicide in 1930). He had been a poet connected with Russian Futurism and called to destroy ‘the old language, powerless to keep up with life’s leaps and bounds’ (Danchev, A., 2011, p.103). In his ‘speech to be delivered at the first convenient occassion’ (Danchev, A., 2011, p.102). He wrote that the year had been ‘a year of deaths: almost every day the newspapers sob loudly in grief about somebody who has passed away before his time’ (Danchev, A., 2011, p.102).

In the late 1970s New York hip-hop scene the tag SAMO (Same Old Shit) attracted attention. The tag belonged to Jean Michel Basquiat (1960 – 1988). Basquiat was a nineteenth-century flanuer with a spray-can in hand. Graffiti artists would bomb trains and tag public buildings, creating a visible space for their voice. By the mid-eighties Basquiat was working on collaborations with Warhol and had taken his work from the streets to elite New York galleries. During this time New York’s Mayor Koch was spending 6.5 million dollars on ‘removing graffiti, while the subway police devoted enormous time and effort preventing its occurrence on trains’ (Mirzoeff, N., 2005, p.163). Graffiti was a challenge to public order and also a

challenge to the values of the white-owned art world. The tags and messages spoke to a disinherited youth as opposed to the ‘world of outsiders who could not’ (Mirzoeff, N., 2005, p.165). Basquiat died from a drug overdose in 1988. His work had crossed over from the people who understood to the racism and hypocrisy of the left- wing art world who seen graffiti as ‘undermining the modernist ideal of the long- contemplated masterpiece’ (Mirzoeff, N., 2005, p.164). The writer Paul Theroux wrote that graffiti was ‘crazy, semi-literate messages, monkey scratches on the wall’ (Mirzoeff, N., 2005, p.163).

A musical composition written in 1952, titled 4:33 by John Cage ‘in which the performer makes no audible sounds’ (Kauffman, D., 2011, p.1) was not according to Cage ‘a mindless stunt designed to bring attention to a composer while undermining the Western music tradition’ (Kauffman, D., 2011, p.1). The idea of the piece, performed in three movements, was to bring the audience’s attention to the sounds around them – that sounds of silence would be heard as music, ‘including the sound of the growing agitation of certain audience members’ (Kahn, D., 1997, p.556). Cage’s compositions were influenced by art, Buddhism and architecture. In Mark Slouka’s essay: Listening for Silence, he writes that Cage’s composition 4:33 ‘attempts to say […] to communicate – what ultimately cannot be communicated’ (Slouka, M., 2008, p.44). According to Kahn ‘instances of silencing create conditions for asking questions, which in turn lead to large transformations in consciousness’ (Kahn, D., 1997, p.570).

Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983) once said that faith ‘is much better than belief’ (Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009, p.398). This is because when one believes – it is in what someone else thinks. He enrolled at Harvard, though was thrown out, once for withdrawing his entire ‘allowance from the bank to romance a girl’ (Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009, p.399) and second time for sheer lack of interest. He later wrote: ‘What usually happens in the educational process is that the faculties are dulled, overloaded, stuffed and paralyzed’ ( Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009). In 1927 Fuller contemplated suicide. What stopped him was a voice he heard: ‘You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the Universe. You and all men are here for the sake of other men’ ( Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009, p.401). The voice that Fuller heard changed him and he went on to create important architectural works and with a team of scientists discovered ‘a new class of carbon molecule’ (Lloyd, J., Mitchinson, J., 2009, p.405) which earned him 47 honorary doctorates.

The German philosopher Hegel believed that the human body stands ‘at a higher stage’ (Knox, T, M., 1998, p.146) it is ‘everywhere and always represented’ (Knox, T., M., 1998, p.146). The ensouled man is a feeling unit with a pulse. The human tint and colour of flesh and veins become ‘the artist’s cross’ (Knox, T, M., 1998, p.146).

The Russian artist Anna Neizvestnova makes paper sculptures of bodies and body parts. The sculptures ‘attempt to analyse the development of symbolic language’ (Neizvestnova, A., 2008) within art. The area of her interest is the

‘explosion of cultural semantics […] gradually becoming a convenient environment for secondary art’ (Nievestnova, A., 2008). Anna’s sculptures are made from text that is connected with the place she is exhibiting. The photo below was taken in Borsec Town Hall, Romania. The sculptures were made from the poems of a local poet, though their silence finally is the enemy of the poet. Though the sculptures are full of movement the words seem dead. What is left are half-words and half-sentences, murmurs crumpled up – the poet’s voice is lost. The sculptures bring to mind Gerald Manley Hopkins sonnet on the Archaic Torso of Apollo. The sonnet focuses on absence. Neivestnova’s sculptures here point to an invisible body, where the lack of torso, genitals and legs point to the mysterious.

The mime artist Marcel Marceau wanted to ‘introduce the magic of silence and imagination to a generation shaped by the noise and action of television’ (Riding, A., 1993, p.1). He refers to himself as ‘the Picasso of mime’ (Riding, A., 1993, p.1). To him, mime is not stronger than words it is merely a choice. Mime cannot easily be described with words it needs to be seen. He says that his ‘aim is simply to make his audience see, feel and hear the invisible’ (Riding, A., 1993, p.2) adding that when ‘mime is not perfect, you see nothing’ (Riding, A., 1993, p.2).

Suzanne Delehanty in her paper Soundings writes: ‘The absence of Sound is silence, the unknown; inaudible voices have always been metaphors for the visions of mystics […] revelations about an invisible world beyond our ken’ (Delehanty, S., 1981, p.)

The Korean contemporary dancer and choreographer Lee Ji Hee’s work embodies silence while her physical state searches for a truth that is linked to the social environment of her performance space. In her work her name is Ji-hee, Lee is stood on a log. Slowly her body negotiates the space, her body feels through an invisible space, that allows her own improvised movement to be freed from the restraints of her gender. The work could be seen as a silent lament, where Lee invites the audience to witness and feel her transformation, which in turn, can only provoke change within their own quiet hearts.

The character Verbal Klint (Usual Suspects, 1995) says ‘The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist. And like that, poof. He’s gone’ (Dir: Singer, B., Usual Suspects, 1995). Perhaps Lee’s greatest trick is how she masks her performance, convincing the audience that this writhing body is her, while the concealed her reaches for a personal relationship with the Supreme. Towards the end of Lee’s performance her dancing legs are reminiscent of Fenand Leger’s Ballet Mechanique (1927).

Bibliography:

Bataille, Georges. 1955, Lascaux or the Birth of Art, (Skira Colour Studio) Baynton, D.C.

1996, Forbidden Signs, (The University of Chicago Press) Ed: Cox, Christopher & Warner, Daniel.

2008, Audio Culture, (The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc)

Delehanty, Suzanne. 1981, “Soundings,” available www.ubu.com/papers/delehanty.html [Accessed: 18/03/2013]

Danchev, Alex. 2011, 100 Artists’ Manifestos, (Penguin Books)

Glenn, Cheryl. 2002, “Silence: A Rhetorical Art for Resisting Discipline(s),” JAC Vol. 22, No. 2, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20866487 [Accessed: 18/03/2013]

Griffin, Jasper. 1998, “Tragedy I,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol:118, http://www.jstor.org/stable/632243 [Accessed: 08/04/2013]

Harrow, Kenneth. 1973, “Caligula, A Study in Aesthetic Despair,” Contemporary Literature, Vol. 14, No. 1, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1207481

Higginson, J. H. 1958, “Sadler’s German Studies,” British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3118534 [Accessed: 21/04/2013]

Ho, Chien-hsing. 2012, “The Nonduality of Speech and Silence,” http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11712-011-9263-9#page-1 [Accessed: 10/04/2013]

Kahn, Douglas. 1997, “John Cage: Silence and Silencing,” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 4, http://www.jstor.org/stable/742286 [Accessed: 10/03/2013]

Knox, T.M. 1998, Hegel’s Aesthetics, Vol.1, (Clarendon Press)

Kuspit, Donald. 1988, The New Subjectivism (Da Capo Press, Inc)

Léger, Fernand & Murphy, Dudley. Ballet Mechanique (1927)

Liu, Fei-Wen. 2004, “Being to Becoming,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 31, No. 3, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805367 [Accessed: 21/04/2013]

Lloyd, John & Mitchinson, John. 2010, The Book of The Dead (Faber and Faber)

Middleton, Richard. 2006, Voicing the Popular, (Routledge)

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 1995, Bodyscape: Art, Modernity, and the Ideal Figure, (Routledge)

Neizvestnova, Anna. https://picasaweb.google.com/109854830219666986564/PaperArt? noredirect=1#5703474408171862178 [Accessed: 01/05/2013]

Prouty, R. 2006, “Walter Benjamin,” onewaystreet.typepad.com/one_way_street/about.html [Accessed: 21/04/2013]

Resnais, Alain. 1955, Night and Fog, (Argos Films)

Riding, Alan. “Offstage with: Marceau, Marcel; Sounding a Legacy of Silence,” http://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/02/garden/offstage-with-marcel-marceau-sounding- a-legacy-of-silence.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm [Accessed: 20/04/2013]

Sandbank, Shimon. 1994, “Poetic Speech and the Silence of Art,” http://www.jstor.org/stable/1771467 [Accessed: 16/03/2013]

Singer, Bryan. 1995, The Usual Suspects, (MGM Studios)

Ed. Tymieniecka, Anna-Teresa. 1994, Allegory Revisited, (Kluwer Academic Publishers)

Winterling, Alloys. 2011, Caligula: A Biography, (University of California Press)

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

Can anyone take this soundtrack and meld it to image?

This piece of music/sound is made entirely from sounds found on a computer lab desktop. I intended it as a soundtrack to an experimental film, however, I seem not to be able to complete the visual half of the project. So – I would like to issue the piece as an open opportunity to the readers of Cinemazine. Can anyone take this soundtrack and meld it to image?

The piece consists of three abstract, imagistic movements. I’m not sure if it is a musical soundscape or found sound based music, but I’d like to know what the results of a collaboration could be.

Right now, the working title is “Scattergories is a Ship of Fools,” but that should probably be changed.

Download the sound clip here (right click to save).

D. Jesse Damazo

Send collaboration projects to sounds [at] cinemazine [dot] com.

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

Locked Groove (2013) is a video installation that I created together with artist Klaus Nyqvist (VJ Klaustrofobia). As a soundtrack I used a silent track of an old vinyl record.

Locked Groove (2013) is a video installation that I created together with artist Klaus Nyqvist (VJ Klaustrofobia). As a soundtrack I used a silent track of an old vinyl record. The silence of the record is actually not silent, the listener will hear the noises of the groove, clicks and pops, scratches, and noise of dirt. All these noises has been accidentally captured on the groove during the decades.

I processed the silence track through active equalizer. The piece starts from the highest noises of the groove (low noises are filtered out) and ends to the lowest noises of the track (where the highest noises are filtered out).

The video is projected on a large screen that is installed on the wall of the gallery. Under the screen, on the floor, is a vinyl record running on the turntable of an old 1960’s record-player. The area in front of the screen is surrounded by four Genelec speakers that distribute the noises of vinyl record. With four speakers it is possible to make full sound field around the visitor.

The basic visual element on the video is black and white vertical stripes. At the beginning of the video the stripes are quite still, but gradually the noises of the vinyl affects to the edges of stripes and they start to shake. When the time passes the movement comes stronger until finally the stripes broke up and the screen is full of broken black and white particles.

The Locked Groove was screened first time in January-February 2013 at the gallery of the Finnish Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. The work has been released on a compilation DVD entitled Muu Video 2013 (Muudvd09-2013).

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

The structure of Earthquake V1 is derived from earthquake data recorded in California and Nevada during a 24 hour period on 3/23/13.

The structure of Earthquake V1 is derived from earthquake data recorded in California and Nevada during a 24 hour period on 3/23/13, culled from the Southern California Earthquake Data Center at the California Institute of Technology. The duration and temporal placement of seismic events were condensed from the 24 hour period down to 10 minutes. The magnitude, geographic location and depth were used to determine the volume, spatial location, sample choice and/or computer generated sound. These works are spatialized for binaural playback and best heard with headphones.

Earthquake V1 is composed of looped samples made largely with contact microphones which include pins dropping in metal and glass containers, sounds created with a handmade aeolian harp, paper being torn, a ceramic tile being scrapped across concrete and spinning coins. The rumble is a manipulated sample of leaves being crunched.

The work is part of a collection called, Salvatore, recently released on the netlabel, Petroglyph Music. http://archive.org/details/petroglyph148PhilipMantione-Salvatore

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

Void or Art? parodies the “art experience” by putting words in the mouth of the viewer.

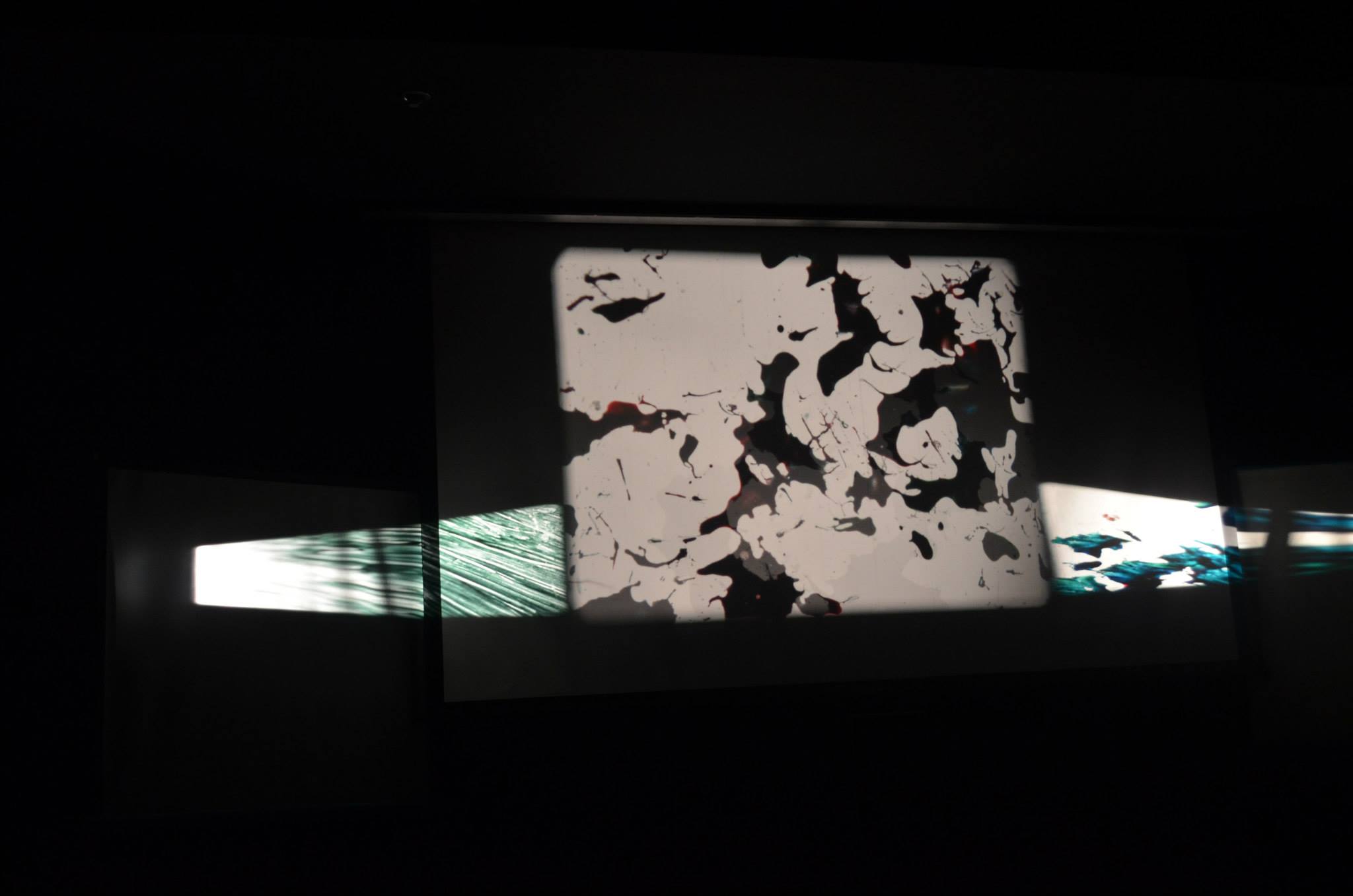

Void or Art? parodies the “art experience” by putting words in the mouth of the viewer. As three hand-painted loops extend the cinematic space toward the viewer, the sound rejects it, then embraces it, critiques it, then contemplates it, and even meets old college classmates in its dialog with itself. — Robert Edmondson

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents