Great question, eh? Should we ruin it with an answer? (1)

I

The derivation of the word “silence” comes from “the absence of sound.” The word “sound” derives from ‘”to be audible.” “Audible” derives from “to hear, to perceive.” “Perceive” comes from “to understand.” And the word “understanding” comes from “mutual agreement.”

Could the relationship between the tree falling and ears hearing it be a mutual agreement? Wait! Did I just hear an audio hallucination from yon transcendental timberland? Nietzche mused, “People have the acoustic illusion that where nothing is heard, there is nothing.”

Listen, author Orlando Battista claims, “There are times when silence is the best way to yell at the top of your voice.” This essay is silence yelled at the top of my voice. (2)

To steal a phrase from Jonathan Lethem’s review of Thomas Pychon’s Bleeding Edge, I use teasing, “much as Pollock uses a color on a panoramic canvas or Coltrane a note in a solo: incessantly, arrestingly, yet seemingly without cumulative purpose.” I yearn for noise about noise and silence about silence, but wind up with much ado about …………

But “let us leave theories there and return to here’s hear,” wrote James Joyce in Finnegans Wake. (3) He hoped that people would read his book aloud, turning the eye into an ear. (4) Was Joyce invoking the spirit of cinema by evoking the staccato stutter of the film projector with the stutter of speech? The Wake makes speech visible. Why do humans have eye lids, but no ear lids?

Wake scholar Laszlo Moholy-Nagy wrote: “We must learn to write acoustic sequences on the soundtrack without having to record real sound. The sound film composer must be able to compose music from a counterpoint of unheard or even non-existent sound.” Filmmaker Mark Hardin responded: “Sounds are intrinsically pure and innocent; imbuing them with subjective distinctions is unfair!.”

II

Noise can save lives. In my hometown Venice, California, a motorist drove his car onto the boardwalk in August 2013, killing one person and injuring over a dozen. A bicycle got caught under his car. The loud scraping sound of the bike on the cement warned people to get out of the way more than the screams and the car noise alone.

I often ride my bike down alleys and must be on high alert for the engine sound of cars coming around corners. I feel it is important for electric cars to add the car sound since society is so dependent on utilizing the noise as a safety factor in avoiding accidents. Motorcyclists accomplish this by revving their engines (or sabotaging their mufflers) whether for safety or just being obnoxious. Motorcycle slogan – “Loud Pipes Save Lives.”

III

John Cage was obsessed with Thoreau’s maxim: “Silence is the universal refuge.” Cage carried on the probing with his own quips: “Everything we do is music,” “There is no noise, only sound,” and my favorite, “I have nothing to say and I am saying it.”

Author Ben Watson wrote, “John Cage’s theory of the nonexistence of silence encourages audiences to listen until their ears ached.” By the way, how are your eyes doing? Cage said, “Music is an oversimplification of the situation we are in. An ear alone is not a being.” (5)

John Cage probed noise as music. In preparing for his famous composition 4’33”, he spent time in silence. As writers on Wikipedia have noted: “An anechoic chamber is a room designed in such a way that the walls, ceiling and floor absorb all sounds made in the room, rather than reflecting them as echoes. Such a chamber is also externally sound-proofed. Cage entered the chamber expecting to hear silence, but he wrote later, ‘I heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation.’ Cage had gone to a place where he expected total silence, and yet heard sound. ‘Until I die there will be sounds. And they will continue following my death. One need not fear about the future of music.’”

It was this revelation – the impossibility of silence – which led to the composing of 4’33”. Though it is usually referred to as the “silent” piece, Cage scholar Richard Kostelanetz says that it should be called the “noise” piece. Pacific Film Archive curator Steve Seid prefers to call it the “noise-cancelling composition.”

Musician David Simons agrees, saying its about “the sounds inside our heads while the concert is progressing. What sounds did we want to hear, and how did we fill the silence?”

Understanding the relationships of sounds can indeed make an impact. In 2010, Cage’s composition charted at number 21 on the UK Singles charts. People continue to love to hate it. I propose an experimental film documenting the performance of 4’33” in an anechoic chamber.

IV

The relationship between noise and silence in avant-garde film and music is fascinating. (6) Having researched psychosomatic cinema for years, I recall that an audience member at a Bruce McClure screening told me that the barrage of loud noise and flickering image caused her period to start. She ran out of the theater feeling as barraged as people who live near airports. The noise becomes unbearable.

Pre-eminent artist Harry Smith hung a microphone out his window in New York City and accumulated environmental recordings for his films. Tony Schwartz, sound archivist supreme, doubled the voice-over narrative which significantly contributed to the the success of the iconic short Frank Film.

Craig “Sonic Outlaws” Baldwin’s mentor Bruce Conner explored the ebb and flow of silence and noise in disrupting societal norms. They both inspired another Bay area experimenter Will Erokan, who employs binaural tones to instigate questions like: “What is silence? Why does it have such a grip on the imagination? And why do we automatically connect it to important parts of the world such as melancholy, memory, solitude, contemplation, and mourning?” (7). These questions are from Helfenstein & Rinder’s forward to the book Silence by Kamps & Seid.

In his 2008 book Canyon Cinema: The Life and Times of An Independent Film Distributor, Scott MacDonald quotes filmmaker Abigail Child: “When I was filming the high school scenes in Mutiny, I was struck by how noisy everything was. The toilet paper roll in the bathroom even sang a little song when you pulled it! It was a sort of revenge that I could make a music out of this noise.”

V

King Crimson’s Robert Fripp said, “Music is the architecture of silence.” Frank Zappa, who called music air molecule sculpting, sang about a pile of radios all tuned to a different station. How Cagey of him! His mentor, Edgard Varese, who spoke of “organized sound,” employed the siren as an instrument in his orchestral music. And Cage wrote, “After I decided to devote my life to music, I noticed that people distinguished between noises and sounds. I decided to follow Varese and fight for noises, to be on the side of the underdog.” Arf!

Atomic dogs George Clinton and Bootsy Collins ride bicycles built for fools. Since they persist in their folly, they become wise and preach, “Funk is the absence of.” They learned about the gap from Sun Ra, who traveled in a rocket ship propelled by music as fuel. The resonating interval between silence and sound can blast one to where the action is. That not-so-silent sea reminds me of music of the spheres, which birthed the echo and epistrophy of Thelonius Monk. He righteously proclaimed, “The loudest noise in the world is silence.” Say what?

The absence of sound is a center without margins. When is it “dead air” (Frank Zappa), “thick air” (Bob Weir) or “colored silence” (Stockhausen) ? Joan Miro spoke Duchampian: “What I am looking for…is an immobile movement, something which would be the equivalent of what is called the eloquence of silence, or what St. John described with the term ‘mute music.'”

Study Stephen Crocker’s revealing essay “Sounds Complicated: What Sixties Audio Experiments can Teach us about New Media Environments” in Janine Marchessault and Susan Lord’s 2007 book Fluid Screens, Expanded Cinema. Quoting Michel Serres’ “hearing is a model of understanding,” Crocker reviews three particular qualities of the sound environment: “the omnidirectional nature of sound, the passive manner with which we receive it, and the kind of organizational structure that results from the mixing together and layering of disparate sounds.”

Crocker details how Glenn Gould told his mentor Marshall McLuhan that the future of piano performances will entail multidimensionality, like The Goldberg Variations accompanied by the white noise of TV sets and radios. (8)

VI

We have been brainwashed into “see say” cinema. The sound matches the picture. Bette Davis insisted how she did not want Max Steiner following her up the stairs in a movie. She wanted to show off her acting skills without musical accompaniment. Can we even take it to more extreme? Why is the Philip Glass arpeggio so mandatory in documentaries. Have we been Koyaanisqatsied? What were the psychic repercussions of Koyaanisquatsi director Godfrey Reggio taking a vow of silence for years?

Remember in Sunset Boulevard, Gloria Swanson states, “We didn’t need dialogue, we had faces.” Lillian Gish commented, “They should have made the silent films after the sound films, because they’re more difficult.”

Sergei Eisenstein asserted, “I think the ‘100% all talking film’ is silly…but the sound film is something more interesting. The future belongs to it.”

One cannot really ever watch a “silent” film in complete silence. The noise in the theater is always present, whether it is popcorn crunching, the whirr of air conditioning vents, the projectionists talking in the booth, and the audience rustling about. Author Kurt London wrote that film music “began not as a result of any artistic urge, but from a dire need of something which would drown the noise made by the projector. For in those times there was as yet no sound-absorbent walls between the projection machine and the auditorium. This painful noise disturbed visual enjoyment to no small extent. Instinctively cinema proprietors had recourse to music, and it was the right way, using an agreeable sound to neutralize one less agreeable.” “Clackety-clack…clackety- clack…” – Film Projector.

Luigi Russolo wrote The Art of Noises manifesto. In 1914, he joined Filippo Tommaso Marinetti to give the first concert of Futurist music, which caused a riot. The program was comprised of four “networks of noises,” titled: Awakening of a City, Meeting of cars and aeroplanes, Dining on the casino terrace and Skirmish in the oasis. In Piano Piece #1 & #2 by Fluxus artist George Maciunas, Ben Vautier hammers a nail through a key on the piano. My band Black Shoe Polish has duct-taped down the key on an electric keyboard to drone for hours. Like Russolo, we feel that noise should not be excluded from music.

Media historian Arthur Knight inquired, “The sight of music becomes the object of industrial mechanisms and forms. The ‘look’ of music influences how listeners categorize what they hear. Is it ‘art’ or ‘commercial claptrap?’ Is it music or noise? What is its relation to me, to us?”

Early jazz piano virtuoso Brad Kay’s observations include: “The substrate of all sound is silence. Without silence, sound does not exist. The difference between ‘noise’ and ‘music’ is whether or not you want to hear it.” Mr. Kay could respond to the neighbor’s construction noise with “Hit the road, Jack…hammer!”

Film director Alberto Cavalcanti affirmed, “Noise seems to by pass the intelligence and speak to something very deep and inborn.” Jazz singer Suzy Williams agrees, but says “noise ” should be replaced with “silence.”

In Bob Marshall’s infamous interview, Frank Zappa spoke of Pauline Oliverios’s work with sound, where she, “created something audible. By combining something so high you couldn’t hear it and something so low you couldn’t hear it, it yielded something in the middle that you could hear. Whether or not you like what you hear in the middle is another question. The concept is brilliant.” Percept as concept?

Tom Snyder asked Jerry Garcia, “Did playing rock affect your hearing?” Jerry retorted, “What?”

Silence is the new loud. Black Shoe Polish funkateer Andre Cynkin wrote, “In counterpoint to Miles Davis, the prince of silence, Jimi Hendrix filled the room with so much sound that he chased away silence — saying, ‘While your ears are still ringing, we’d like to continue on with another number.'”

Citing the film theorist Sigfreud Kracauer, influential filmmaker Arthur Lipsett wrote, “Throughout this psychophysical reality, inner and outer events intermingle and fuse with each other – ‘I cannot tell

whether I am seeing or hearing – I feel taste, and smell sound – it’s all one – I myself am the tone.’”

VII

In 1967, Gerald E. Stern asked “Will there ever be silence? And Marshall McLuhan responded, “Objects are unobservable. Only relationships among objects are observable.”

In preparing this essay, I received an enlightening comment on this McLuhan response from the provocative sound artist Frank Pahl: “The McLuhan quote is related to Einstein’s theory of relativity in my mind. I can’t help but think that you’ve skipped an aspect of silence that opens a new can of worms. Sound and silence are measurable because they are time based. Global time became synchronized in 1913. Maybe our tools have made silence impossible. If everything can be measured down to the nanosecond, maybe the only way to experience silence is to turn off our brain clocks. Ain’t gonna happen.” Percept as concept?

Samuel Beckett said, “It is all very well to keep silence, but one has also to consider the kind of silence one keeps.” Ssshhhh! “Beckett was addicted to silences, and so was Joyce; they engaged in conversations which consisted often of silences directed towards each other, both suffused with sadness, Beckett mostly for the world, Joyce mostly for himself.” – Richard Ellman’s James Joyce. Sam sensed, like McLuhan, that words are necessary to explain that words are unnecessary, so forget this whole essay, right? “Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness” – Beckett.

Thomas Pynchon wrote “Come-on! Start-the-show! The screen is a dim page spread before us, white and silent.”

Simons told me that the word “silence” is “from Latin ‘silentium’ an element, like ‘unobtainium.’ You don’t know if it’s ever there, or measurable. Maybe silence is only a state of mind. But when you do experience it, it’s real LOUD. It’s ironic but true that so much could be written about silence.”

What haven’t you heard lately?

+++++++++++++++++++++++

Let’s call these “earnotes” instead of “footnotes.”

(1) “That is a very good question. I should not want to spoil it with an answer.” – John Cage, Lecture on Nothing, 1959

(2) Inspired by McLuhan’s Menippean mosaic writing and Burroughs cut-up technique, this exercise in pattern recognition probes sound and silence in quest of comprehensive awareness. Artist-Heretic-Savant Walter Alter observes, “Mosaic implies composite rather than continuum, which echoes how our psyches are constructed, or at least accessed when we try to remember- we try to recall telling bits and pieces of a memory or idea until it somehow self assembles and we go ‘Ahah, there it is’ when we’ve finally recalled what we were searching for. Mosaic implies autonomy in that we are free to assemble and dwell upon the elements of the mosaic as we wish or are able, and not as a propagandist might want us to. Mosaic also implies a freedom to associate their elements to one another as we wish, both ideationally and potentially in a different sequence than presented by the author.”

Mosaic writing can imply collective thinking or writing by committee. In efforts to better understand the relationship of mosaic writing and collective thinking, I ponder my friends’ input. One of my favorite reactions: “Maybe add, early on, the standard/dictionary definitions of silence and noise? As the cantus firmus upon which your fugue takes flight? Or just as a set up to ask the dictionaries to ‘Shut up!’ Maybe mix in a comparison of the structure of sound/music and the structure of logic, showing how theorems and postulates are put forward in both, tested and vetted then put forth as truth? Maybe talk about the asymmetry of sound and silence, where sound can murder silence but silence can’t return the favor? Do we assume a hierarchy because of this, incorporate an idea of relative strength? (Of course) Add a cameo by Captain Beefheart: ‘I use music to sculpt thought.'”

(3) http://laughtears.com/wakedreamawake.html (program notes for Fialka’s workshop – “Dreaming Awake: How James Joyce Invented Experimental Cinema and Disguised it as a Book”)

(4) This is an example of sense-ratio-shifting, much like Joyce’s “where the hand of man never set foot.” In fact, he was keen on three words, “silence, exile, cunning” as weapons of art-making.

(5) Jean Epstein wrote, “Like the eye, the ear has only a very limited power of separation. The eye must have recourse to a slowing down. . . . Similarly, the ear needs sound to be enlarged in time, i.e., sonic slow motion, in order to discover, for instance, that the confused howling of a tempest is, in a subtler reality, a manifold of distinct noises hitherto alien to the human ear, an apocalypse of shouts, coos, gurgles, squalls, detonations, timbres and accents for the most part as yet unnamed.” David Simons reacted to this Epstein with his own: “What is Prismatic Hearing? When light travels through a prism it is broken down into its component parts. When a sound or a statement enters a person’s ears, it is fed into the prism of the brain. A person must subjectively ‘reference’ the sound. Upon hearing the component parts of this sound, the brain then re-assembles it into what may likely be its’ closest audio approximation. This prismatic interpretation depends on a number of factors, including creative bias, actual hearing malfunction, poetic license, etc. In many cases the prismatic hearing results in a more interesting phrase than the original. ”

(6) Steven Woloshen’s thoroughly annotated bibliography surveys sound in avant-garde filmmaking ( http://cinemasound.wikispaces.com/Woloshen ). I suggest getting knee deep in studies of Marcel Duchamp, Len Lye, Cecile Starr, Gene Youngblood, Mary Ellen Bute, Robert Breer, Martin Arnold, Oskar Fischinger, and, especially, Stan Brakhage’s quest to relearning to hear, and Hollis Frampton’s use of “contrapuntal” or “over tonal” sound relationships. As Octavio Paz wrote about Duchamp, “The Bride is an imprecise auditive and mental reality…an ambiguous optical and mental reality.” Duchamp said, “She is virtual sound,” and Paz added, “an echo and a silence.”

(7) “We must now ask some very different questions about the relationship between music and life.” – Anthony Burgess.

(8) Poet/politician Robert Dobbs reports that, “Ezra Pound told his father that the fragmented nature of his Cantos should be experienced as one experiences the disembodied voices of a radio drama: ‘Simplest parallel I can give is radio where you tell who is talking by the noise they make.’”

+++++++++++++++

Special thanks to Jules Minton, Suzy Williams, and Hear Comes Everybodies.

Gerry Fialka lectures world-wide on experimental music, film, avant garde art, and subversive media. Laughtears.com

++++++++++++

More:

“The rest is silence”, the last words of Prince Hamlet in Shakespeare’s play Hamlet.

Joshua Oppenheimer, director of The Act of Killing, said: “Film is a shitty medium for words. Film is a good medium for silence.”

Author Ben Watson wrote, “John Cage’s point that any noise can be musical because noise can be subjected though the parameter of duration.”

Eckhart Tolle says that silence can be seen either as the absence of noise, or as the space in which sound exists, just as inner stillness can be seen as the absence of thought, or the space in which thoughts are perceived.

From the journal RENASCENE, in words that echoed T.S. Eliot’s definition of “auditory imagination,” McLuhan’s article treated “words not merely as signs but as things with a mysterious life of their own which could be controlled and released by establishing exact relationships, rhythmic and harmonic, with other words.”

“The deepest feeling always shows itself in silence.” – Marianne Moore

“In the breach the note sounded, and then the silence sounded.” – Edna O’Brien

“The notes I handle no better than many pianists. But the pauses between the notes—ah, that is where the art resides.” – Artur Schnabel

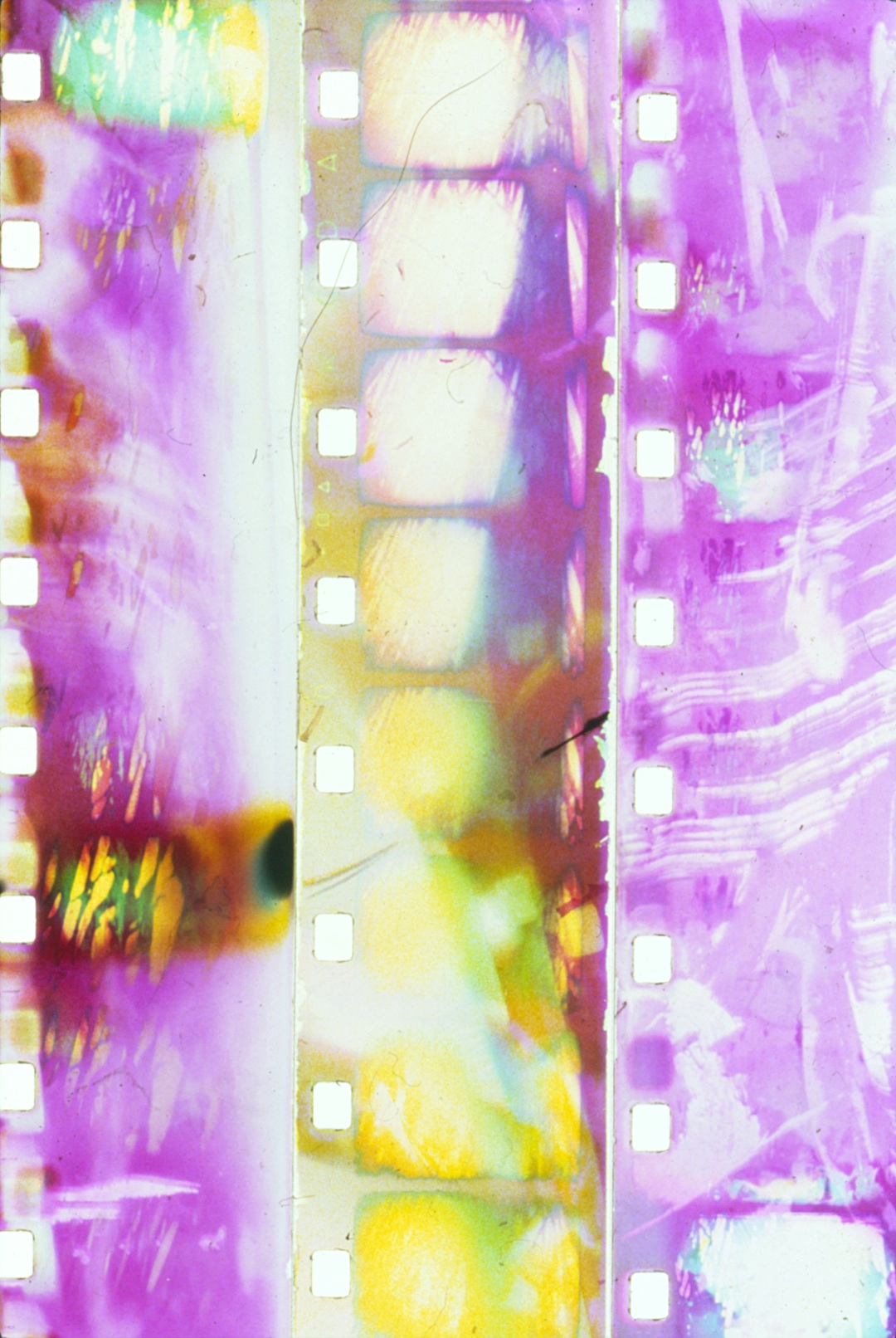

*** The image that accompanies this essay is entitled “Noise Floor – Sergei Eisenstein in Mexico, 1930. Photographer Unknown.” Collage by Gerry Fialka.

The term “noise floor” refers to the unintentional, incidental hissing sound made when a movie projector reads and amplifies the ostensibly silent optical audio soundtrack on a piece of film; one of the advantages of magnetic or digital film soundtracks in 35mm film is the dramatic reduction or elimination of the noise floor.

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents